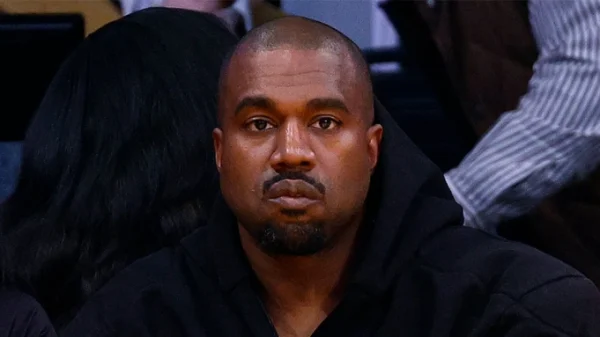

Kanye West, one of the most popular, influential and commercially successful musicians of the past 20 years — who has effectively set his businesses and career on fire with a series of indefensible anti-Semitic comments — is currently without a record label or a music publisher. Universal Music’s Def Jam Recordings and Sony Music Publishing are both out of contract with him, and many of his other business partners have broken ties in the wake of his recent behavior. On purely music-business terms, the situation is unprecedented.

Def Jam, which owns the copyright to his recordings up to sometime in the mid-2010s and distributed subsequent releases up to last year’s “Donda” album, has confirmed that his deal with the company ended last year. (The copyright credits on some albums have changed in recent weeks; it now appears that West owns his masters from the 2013 “Yeezy” album onward.) As with RCA Records and R. Kelly, the company will continue to own and/or distribute his catalog, and profit from it, per the terms of their contract. Def Jam presumably owns the recorded-music rights to his earlier recordings for decades to come, although it is unclear when the post-2013 releases will be up for a new distribution deal.

Sony Publishing confirmed that his administration deal with the company ended earlier this year, although it will continue to administer his work, per the terms of the deal, for an unspecified time.

So what happens when he wants to release new music? He has released three songs in collaboration with other artists this year (all before his anti-Semitic comments), but all were on his collaborators’ labels — a scenario that is less easy to imagine now.

Presumably, based on his recent comments about launching his own apparel lines, he will put the music out himself. But releasing music on Kanye West’s level requires major business partners — who will work with him?

While the majors — Universal, Sony and Warner Music Groups — are likely out of the equation for the foreseeable future, it’s possible that he could strike a deal with a large indie like the hip-hop powerhouse Empire, Create Music Group (which distributes Tekashi 6ix 9ine releases) or France-based Believe, which is one of the few Western music companies that did not shut down or drastically reduce its operations in Russia after the invasion of Ukraine earlier this year.

However, those or similar companies would have to brace for serious fallout. “It would have to be someone willing to be ostracized,” one veteran music industry executive says. “The other artists on the label or distributor, not to mention the staff, probably wouldn’t stand for it.” (Reps for those companies did not immediately respond to Variety’s requests for comment, although one said that many of their company’s staffers would have strong opinions about such a move.)

It is certainly possible to work within the label system on a per-release basis: Prince managed to avoid signing with a label for the last 20 years of his career — owning his masters and licensing some releases to majors, others to larger independents and others simply on the internet — although he did not carry the baggage that West does.

However, it’s easy enough for an artist of West’s stature to simply post music and not worry about traditional distribution, radio play or even manufacturing CDs or vinyl. If he weren’t able to find a partner, he could simply make an announcement on social media and upload the music to virtually any streaming service, as long as the song did not include what Spotify terms as “hate content” or anything that otherwise violates the services’ policies; most do not bar an artist based on their conduct, but rather the content of the music. The streaming services all pay royalties to the rights holders, which is usually a label but in this case would be West and anyone he might partner with.

The publishing, however, is a more complex issue. Tracking down and collecting publishing royalties, which is known as administration, is a complex and laborious operation that requires extensive infrastructure; even a large publisher like Primary Wave Music outsources it to major companies like Universal and Warner.

Some of the work is relatively automatic: Mechanical streaming royalties are collected by the non-profit Mechanical Licensing Collective, and he continues to be affiliated with performing rights organization BMI (which even named him songwriter of the year at its Trailblazers of Gospel Music Awards in 2021), which per its mandate cannot terminate a relationship with a songwriter.

In a statement provided to Variety, a BMI rep said: “Antisemitism, racism and hate have no place in our society, and we condemn the harmful and dangerous rhetoric from Kanye West. Under the terms of our consent decree, BMI is mandated to accept all songwriters who want to be a part of our organization. Our fulfilling this mandate does not condone any individual’s hate speech.”

However, relying only on mechanical and performance royalties is to leave a vast amount of money on the table — possibly reaching into the millions with a catalog like West’s.

At this point it’s hard to imagine a major publisher — or even a smaller one — agreeing to work with West on even a for-hire basis, although it probably could be done under the radar for a period of time. It’s possible that he could use a semi-automated music-licensing company like Songtradr, which uses technology to track and monetize catalogs, or strike a deal with a larger company like Downtown Music or Kobalt, which have artist-services divisions that handle everything from physical product to publishing administration. (Reps for those companies did not immediately respond to Variety‘s requests for comment.)

However, those situations are “very passive models,” another veteran industry executive says. “There’s almost no direct interaction between the company and the artist; they collect for a fee and pay out the balance. Someone needs to be overseeing the catalog, being proactive and fielding incoming [opportunities], especially for one as big and lucrative as his.”

Perhaps the most likely scenario would be West either acquiring an existing publishing company to provide that infrastructure for him, or, even more likely, hiring a small staff to handle those duties. West is far from destitute and probably will not be for some time, despite seeing his net worth skydive by an estimated $900 million according to Forbes (or $2 billion according to himself).

“A handful of people would suffice and I’m sure he could find [professionals],” a different veteran executive says, “but revenue would still drop pretty dramatically.”

Of course, there’s another option: to sell his catalog. Reports emerged several weeks ago that representatives for West were exploring that possibility, and although he denied it, the New York Times cited sources earlier this week saying it was true. But although there has been a booming market for song catalogs in recent years — peaking with Bruce Springsteen selling his for a reported $600 million — it seems safe to assume that West’s music has dramatically dropped in value, along with that of his apparel and footwear brands. And if major companies are shying away from going into business with him, they seem just as unlikely to be interested in acquiring and marketing his catalog.

“He denied [exploring a sale] a few weeks ago, but his finances have clearly become more stressed,” the executive continues. “And there are many valuation questions, particularly the toxic equation impacting future earnings — and future earnings are what investors are most concerned about. These unprecedented moral issues raise a lot of questions about risk.”

Finally, if West were to attempt to go on tour or stage any live performances, he would likely encounter a scenario similar to the one faced by R. Kelly in the waning years of his career. Kelly played a series of concerts to die-hard fans arranged with local promoters — bypassing larger companies like Live Nation and AEG, which ordinarily handle tours by artists of that caliber — but those increasingly were canceled as the outcry from fans and others led promoters to cut their losses. It is also unclear what impact West’s anti-Semitic comments may have had on the dozens of people who have performed or participated in his Christian-themed Sunday Service gatherings.

It is hard to imagine how West comes back from the events of the past few weeks. He has always been a contrarian and a provocateur, increasingly to his detriment in recent years, and he has rarely apologized for anything publicly. It’s possible, if unlikely, that once this latest episode is over, he could become contrite, apologize and try to win back the fans he has lost.

“Could he come back? If he apologized and seemed truly, convincingly regretful, it’s possible — possible,” one executive says. “But it would take a long time. It’s hard to imagine him ever approaching his previous standing as a musician or a businessperson. There are some things you just can’t un-say.”

[via]