The first thing Selma Blair says is “How are your spoons?” and I feel myself relax just a little. It’s the last Friday of September, and I am across from her in the sitting room of her house. Blair is wearing riding boots and a linen shirt, her bleached blonde bob hanging above the collar. “I can’t be

The first thing Selma Blair says is “How are your spoons?” and I feel myself relax just a little. It’s the last Friday of September, and I am across from her in the sitting room of her house. Blair is wearing riding boots and a linen shirt, her bleached blonde bob hanging above the collar. “I can’t believe I went my whole career without ever being nervous for an interview,” she says as we sit down. Until now, that is. Her voice tilts and crashes on different syllables before lifting up again, marked by the spasmodic dysphonia that accompanies a flare of multiple sclerosis. Yes, she seems nervous.

So the spoons: Spoons are a shorthand way for chronically ill and disabled people to explain and ask each other how much energy they have on a given day. My heart warms (genuinely, it warms—I feel it in my chest) when she asks me how mine are because underneath the question is something else that doesn’t need to be explicitly said: I know you are like me

lieve I went my whole career without ever being nervous for an interview,” she says as we sit down. Until now, that is. Her voice tilts and crashes on different syllables before lifting up again, marked by the spasmodic dysphonia that accompanies a flare of multiple sclerosis. Yes, she seems nervous.

So the spoons: Spoons are a shorthand way for chronically ill and disabled people to explain and ask each other how much energy they have on a given day. My heart warms (genuinely, it warms—I feel it in my chest) when she asks me how mine are because underneath the question is something else that doesn’t need to be explicitly said: I know you are like me

And I am. I’ll get this out of the way quickly (because who wants to read about me when you could be reading about Selma Blair?): I have chronic migraines that completely disrupt every part of my life and also a history of thyroid cancer and traumatic brain injury. Like Blair’s, my body does not move through the world in an orderly way. Both she and I live at the mercy of our bodies’ whims. And we are both trying to believe our own pain, after decades of being told it wasn’t real.

Blair was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2018 at the age of 46. Looking back, she sees the fingerprints of the disease—which causes a person’s immune system to attack the sheath covering their nerve cells—all over her life. With the diagnosis, so much suddenly made sense: her childhood reputation as a sensitive, attention-seeking child, which she sees as stemming from her nascent pain; her struggles with alcoholism, which began at the age of seven and which she now recognizes as an attempt to cope with her symptoms; her efforts to meet the demands of work and motherhood and life. She has been sober since 2016. “In my mind, I thought, You can’t keep up with people. You are broken. This is your fault. You are lazy,” Blair tells me. “It was so much self-loathing.”

The diagnosis was a revelation. Whether the rest of us will understand what its physical manifestations can look like day-to-day—that’s what worries her. “Once I got really hit with the more neurological stuff, everything shifted,” she says. “I spin my wheels thinking, Oh my God, I’ll fall asleep in front of someone. I won’t do well enough.”

It’s a fear she has decided to push through, at least for the purposes of this conversation, so that she can explain: “It was a relief,” she says of the news that she did in fact have MS. “I couldn’t believe I was getting a legitimate diagnosis that other people would believe. It was like, Oh my God, there’s a receipt.”

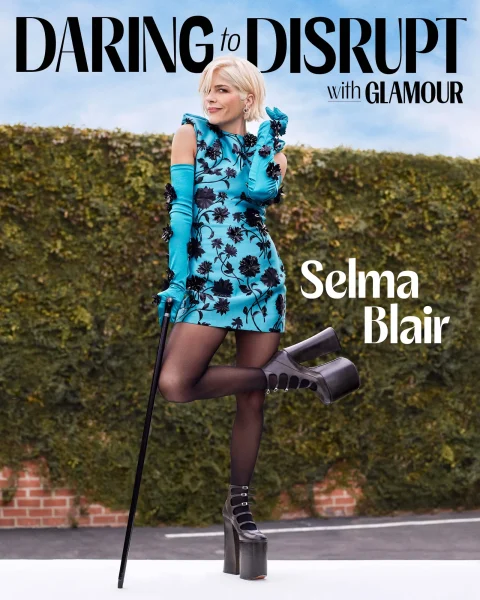

he lens of Blair’s condition offers an important reframing of her early career. Although she landed her first lead role in the film Strong Island Boys in 1997, it was her breakthrough performance as Cecile Caldwell in Cruel Intentions in 1999 that made her truly famous. The film earned her an MTV Movie Award and became a cult classic. (Perhaps its success softened the blow of losing the role of Joey Potter on Dawson’s Creek to fellow newcomer Katie Holmes the year prior.) In 2001, Blair—reunited with her Cruel Intentions costar Reese Witherspoon—solidified her place in the millennial film canon with Legally Blonde. Her portrayal of Vivian Kensington was the perfectly preppy foil to Witherspoon’s Elle Woods. Yes, she is still friends with Witherspoon, who is, yes, as angelic as she seems. “She’s so clean,” Blair says. “I don’t know how to say it. She’s the most pristine [person]. When she sweats, I’m like, ‘What are you wearing? Where is that scent? Where can I buy it?’”

This should have been, in many ways, the beginning of Blair’s ascent. And a number of solid roles followed, including Hellboy in 2004, in which she played a magnetic and depressed superhero. It’s a role that’s meaningful to Blair for many reasons, including the fact that it was her last high-profile part before her physical pain really intensified. She remains struck, too, by the insightful pronouncement of the film’s director, Guillermo del Toro, who observed her and said: “You and Joaquin Phoenix are the only people when we say action, you turn away from the camera.”

“I’ve never been seeking the light,” she says. “I always turn away from it when I know the light is what will make me shine.”

During the following four years, Blair kept working, mostly in supporting roles. Then, in 2011, before she had a name for her pain, she had her son, Arthur, and her world as she knew it fell apart. She and his father, designer Jason Bleick, split after his birth. She is careful, talking about this period, but she is also frank. It was a shattering time

“The MS flared very obviously, when I was in labor,” she says. “My body started going through distress as bodies can, and, of course, I didn’t know I had it. And so the moment Arthur was born, I went from this kind of blissful pregnancy to utter devastation.” Blair didn’t know how she would get through a single day, let alone the months ahead. “Everything was too overwhelming,” she says now. “I couldn’t be in a relationship. There was nothing I could do except be a mother. And I was brutally tired and I didn’t have a support system. I didn’t know how to set one up.” She still identifies as a “long-time loner,” an identity she traces back to being a sick kid. “You get used to kind of having your schedule and it doesn’t jibe with people,” she says. “So even though I’m sociable and friendly, I’m alone for everything. And this child automatically became my biggest responsibility, my biggest love, but it was a very, very hard adjustment for me. Very hard

Blair did consult with doctors, who informed her that it was “normal” for new mothers “to be in pain all the time.” She went to conventional experts and holistic practitioners, and she reported her symptoms: “I cannot stay up. I cannot drive a car. I cannot see. I’m bumping into things. I’m dragging my legs.” Some chalked it up to stretched tendons from labor. Others suspected postpartum depression, which Blair is adamant she didn’t have.

Now she recognizes her slate of symptoms as “pure exhaustion, an MS flare,” but she had no language for it then. What she did know was that she was “broken down” and jobless. “I was totally out of the workforce, and I couldn’t earn money,” she says. She believed the experts, who amplified her sense that she was just too fragile, that she couldn’t hack it like regular people could. Eventually she called her manager and said, “We have to get me a job.” She did get several, including a starring role on the sitcom Anger Management (until it was widely reported that Charlie Sheen fired her via text message) and commercial gigs. But the work was sporadic and her physical agony was acute. “I was forcing myself on a plane, and I was getting vertigo,” she says. “I would wake up, and I couldn’t move.”

It was a very hard time in my life,” she continues. “But it was the catalyst to become who I am now.”

In a sense, 2018 was an end and a beginning. The diagnosis marked the resolution of decades of yearning and searching, of pain and disbelief—on the part of not just the doctors, but herself and the doubts she harbored. No wonder it’s just now that she’s started to find her light.

She spent the next few years filming the documentary Introducing, Selma Blair, which was released in 2021. It’s a starkly candid project that chronicles her life in the months following her diagnosis, and it’s often not pretty. In one scene Blair lies in bed ahead of a round of preliminary chemotherapy, which she was prescribed as part of a treatment known as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, a high-risk procedure that aims to rebuild a person’s immune system. She has been crying. Her eyes are red, and her voice is thick from crying. “I was told to make plans for this,” she says. “For dying.”

Living in a sick body intrinsically requires a high level of exposure. In illness, doctors ask hyperpersonal questions, your body is poked and prodded and operated on, sometimes your symptoms flare in public. For Blair, as an enduring celebrity, that experience is heightened. I can’t help but wonder whether she ever wishes she’d kept it to herself. There is nothing more intimate than being sick, and she has welcomed cameras—and journalists like me, asking her this question right now—into her private world. Does she wish she hadn’t? “No,” Blair says. “Because I already was disabled and didn’t have a word for it.”

Instead, she is pursuing unshrinking honesty. Even when—especially when—it forces her to confront people’s biases and the ableism she is still unlearning in herself. Does she look enough like a sick person, she sometimes wonders? She summons the judgment of her critics: “This fucking Karen, talking about disability, and look at her or carrying a coffee, walking a dog. She shouldn’t carry a coffee while walking that dog! If she can carry a coffee, she shouldn’t have a service dog!”

I just have to think, What can I do, so this can happen less to other people?” It has become, as she puts it, “a personal point of necessity to stand up for other people when I wouldn’t stand up for myself.”

It’s been five years since Blair first shared her diagnosis, an announcement she made on Instagram. Five months later she walked the red carpet of the Vanity Fair Oscars party, wearing a chiffon gown. She was photographed with a diamond-embellished cane and looked more at home in front of the cameras than she had in years.

In 2022, following the documentary, Blair took part in Dancing With the Stars. In a previous interview she recalled she told her manager: “I think it’s important for people with chronic illness or disabilities to see what they can do. I deserve to have a good time and try.” That same year, she released her memoir, Mean Baby, in which she details her childhood as one of four daughters born to a mother who comes across as critical, demanding, and Blair’s “first great love.” The book follows her move to Hollywood, her path to finding a name for her illness, and her resolve to live alongside it.

Make no mistake: Mean Baby isn’t an epilogue. There is still so much Blair wants to do. She’d like to date again, for starters—something she hasn’t done since she was diagnosed. “I had a bad relationship,” she says, by way of partial explanation. “I didn’t realize how emotionally abusive and controlling they were, taking advantage of meeting me in a really vulnerable time.” She isn’t necessarily surprised that she put up with it, but it does make her sad. “I was convinced that’s what I deserved,” she says. “When you’re in a rough spot, you can meet some opportunistic people. It’s really dangerous.”

She has just started to feel ready for romantic possibility, but she knows the obstacles. “I think the disability word, because I said I was—it just confuses people,” she says. “Like, as if I don’t have a vagina.”

Recently she met a man at a friend’s birthday dinner. It was exciting. “Something in this person inspired me to see myself differently by the way he looked at the world,” she says. “Just from that brief meeting, I thought, I have something I didn’t know I did.” She’d like to find him, so consider this a missed connection: Are you this man? Call Selma Blair.

“What [being in love] does for your spirit—it’s nothing to take lightly,” she says. “It colors everything. I still believe if I’m just true to myself, that person will come into my life one day.” And moreover, she adds, “I think I deserve it and think I’m in a great place to show up as the best version of me. It’s the first time I have hope. And I could have never said that in my life before.”

She has other ambitions too. She’s embraced disability activism by working with the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America and the American Association of People with Disabilities. She’s also developed friendships with people such as Andraéa Lavant, a disability-inclusion specialist who consults with brands and on movie sets. But the work has also forced her to confront the career she more or less left behind. “I had to realize I do love acting,” Blair says. “I really would love an amazing director to ever think there’s something for me.” She has been experiencing “all those little-girl things you feel when you first come to Hollywood”—the dreams, the intentions. “I still feel like I never really hit my stride with acting because after Hellboy I was so sick that I really stepped away. And because I wasn’t a huge star, no one came looking.”

“I do wonder, practically,” she says, no doubt thinking of the cane and the service dog and the lilt in her voice. But she has noticed that she deals with less dysphonia if she knows exactly what she wants to say. She could memorize lines, she thinks.

“I think that’s the key with everything,” she says. “Really get comfortable with yourself and it doesn’t matter if you falter, because you know where to pick yourself up again.” She is finding her footing, she continues. “I have such a fucking determination.”

The beauty of this particular moment, however, is her knowledge that embracing the old parts of herself doesn’t mean renouncing her new reality. In 2022 she also signed on as chief creative officer of Guide Beauty, which creates accessible beauty tools. And, a well-documented clotheshorse, Blair has become a QVC brand ambassador and launched an accessible (in every sense) collection in collaboration with Isaac Mizrahi. The line is a natural fit for Blair, who can wax poetic about a particular vintage Schiaparelli dress in her closet. The new clothes incorporate access-oriented elements like magnetic closures and pants fitted for wheelchair users. She tells me she is in love with what she and Mizrahi have made. “Disability does not seem escapist,” she says. “But I love clothes. I love pretty people doing pretty things.

Doesn’t the disability community deserve fashion with a capital F? “How do we do the things that are the things we talk about with each other every day?” she says. “That’s the light stuff.” She sees it as her task to “fight for the lighter things for people too.” It’s not, “Oh, clothes, whatever,” she says. “It’s like, No, that’s how I feel comfortable. I love that stuff.”

This is the task of Blair’s postdiagnosis life: balancing the needs of her body with the renewed ambition that disability has sparked in her. Recently she attended to the former by deciding to try ketamine, which some experts think can reduce inflammation and help build neurotransmitters in the brain. Blair has long feared psychedelics, but she wanted to trust her body enough to take it on an adventure. She did it with supervision, in a safe environment. The process ultimately amazed her. “It made me think, Oh God, there’s room for joy. I could learn to build joy here.”

And then there’s the latter—her desires, the future. She has her activism, her son, and her goals. Spending time with Arthur, who has “the empathy of a saint,” is a particular pleasure. From her new vantage point, she can also now see how disability is a spectrum, and the ways in which it’s coming for all of us. “If we’re lucky enough, we all know we’re all going to be in some form of disability or needing someone,” she says, “so let’s break that down now, and enjoy what everybody who’s lived a long time can offer us, because it does get better as it gets worse. You better see both, people!”

After all this, did Selma Blair ever think she’d find gratitude? “Life is wild,” she says, with a laugh. “I’m glad I stuck in there.”

SOURCE:glamour.com