In curving galleries designed by David Adjaye, artists are putting Africa firmly on the biennale map.

The Venice Art Biennale, the world’s most celebrated international art event, has a history that is inextricably bound up with colonialism.

Its first pavilion for the showcasing of a “national” art was established by Belgium in 1907. Britain followed soon after. European countries remain dominant at the event – at least numerically.

And although states such as China have in recent years begun to present prominent national pavilions, African countries have been thin on the ground.

This year, however, that balance is subtly shifting: Ghana has burst on to the scene with an exhibition featuring artists based in the country and from its diaspora.

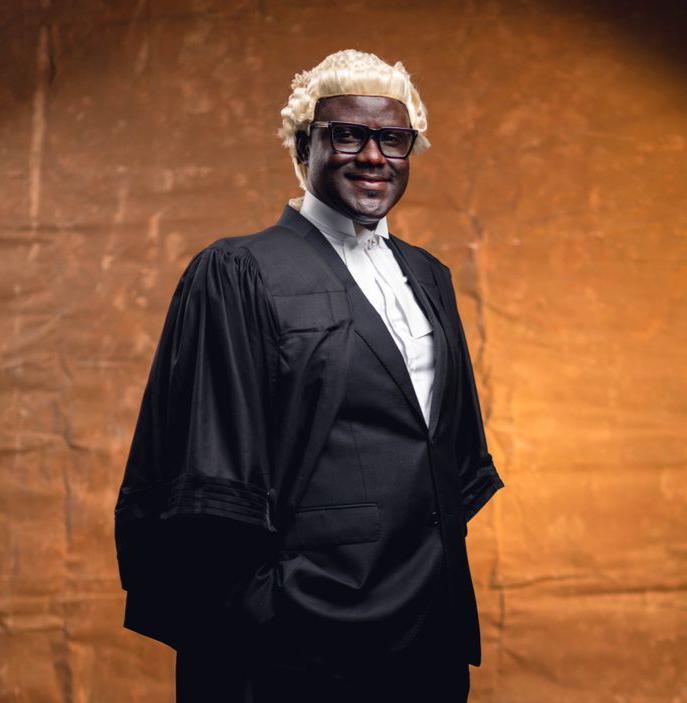

The paintings, photographs, films, sculptures and installations are presented in a series of deftly curving spaces designed by the architect Sir David Adjaye, whose most celebrated work includes the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC. He is also the architect of a planned interdenominational National Cathedral of Ghana.

The impulse to present a national pavilion came from conversations between him and art historian, filmmaker and writer Nana Oforiatta Ayim, the project’s curator.

Their feeling was, said Adjaye, that “Ghana’s cultural production is bigger than the punch it has internationally.

That’s what we said in our presentation to the government – that Ghana’s cultural capital in the world is not being celebrated. And they supported us willingly.”

The first-ever Ghana pavilion officially opened on Wednesday in the presence of the country’s first lady, Rebecca Akufo-Addo.

The artists shown include Turner-prize-nominated painter Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, and Nigeria-based, Ghana-born El Anatsui, who is exhibiting some of his glimmering sculptures made from reused bottle tops.

There is also a series of black-and-white studio portraits from the 1960s and 70s by Felicia Abban, now 83, who was Ghana’s first professional female photographer.

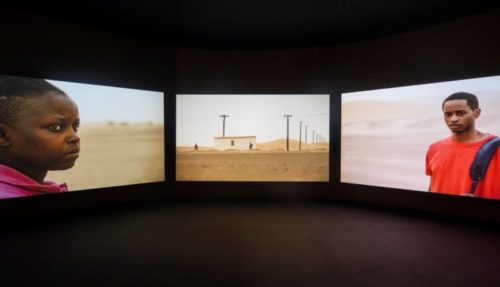

The lineup is completed by Ghana-based artists Ibrahim Mahama and Selasi Awusi Sosu, and British filmmaker John Akomfrah.

Akomfrah called the pavilion and its contents “a charismatic example in a sea of whiteness”.

He added: “In my view, art is a dialogue. We have the biggest conversation on the planet here at Venice, and we wanted to be part of it. Not because Ghana is more unique than any other African country. We just wanted to do it as best we can.”

It can be a politically and intellectually fraught business to present a pavilion of “national” art at the Venice Biennale. Some countries use the event as an unapologetic opportunity for polishing a tarnished image.

Others, in an attempt to recognise their own histories, may find ways to undercut the inherent nationalism of the event – by, for example, inviting artists from other nations to show in their pavilions, or by representing less dominant voices from within their own borders.

This year, for example, Canada and Finland have presented, respectively, Inuit and Suomi art in their national pavilions.

“A national pavilion may not be a straightforward idea if you started [at Venice] 100 years ago,” said Adjaye, “but Ghana is 60 years old, and learning how to be a nation.

A national pavilion is really important in creating that narrative.”

The exhibition is titled Ghana Freedom, after ET Mensah’s song composed as the country was established in 1957, the first sub-Saharan African country to gain independence from colonial rule.

But the title might also be seen as a statement about artistic freedom, and about the freedom inherent in the idea of Ghana, which, as philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes in the exhibition’s accompanying book, is a particularly “diffuse and diverse” country.

Many communities inhabit Ghana, and many Ghanaians live outside its borders.

Oforiatta Ayim, who, with Adjaye, is also advising the Ghanaian government on establishing a new museum, said: “It feels bigger than an exhibition. We’ve all been fighting so hard to do what we’re doing, and now we’re doing it together. That’s where the energy comes from.”